I’ve been using SFML now for more than a year but I never really understood how sf::View really works, until now. So I feel like sharing this enlightenment and I’ll also create a tutorial in the wiki section on GitHub.

What can a sf::View do?

This question is not that complicated to answer and I would’ve already been able to do so a few weeks back but I never really understood how sf::View works. The answer would be a description, so here you go:

A sf::View is basically a 2D camera i.e. you can move freely in two dimensions, you can rotate the whole scene clockwise or counterclockwise and you can zoom in and out but there’s no tilting or panning. Furthermore zooming really means enlarging the existing picture rather than closing in on something. In short terms there’s no 3D interaction.

Examples

So if you now want to move a sprite around without altering its coordinates but instead moving the 2D camera, you could do this easily by calling:

view.move(360.f, 360.f);

Next you maybe want to get a closer look at something, so you can use:

view.zoom(0.1f);

Or you want to rotate everything:

view.rotate(20.f);

Now you get the idea what the camera can do and you’d probably be even able to program something with it, but do you understand how it works? Do you know what the center of the sf::View is?

So let’s get a bit more technical.

How does sf::View work?

So lets see what the documentation of SFML says about this:

A view is composed of a source rectangle, which defines what part of the 2D scene is shown, and a target viewport, which defines where the contents of the source rectangle will be displayed on the render target (window or texture).

The viewport allows to map the scene to a custom part of the render target, and can be used for split-screen or for displaying a minimap, for example. If the source rectangle has not the same size as the viewport, its contents will be stretched to fit in.

If you’ve understood everything then congrats! I didn’t (at first) and although it’s a good, short and precise description it’s not very intuitive.

From the text above we can extract that there are two different rectangle defining the sf::View: a source and a viewport. What we also have, although not ‘physically’, is the render coordinate system, i.e. the coordinates you use to draw sprites etc.

At first I’ll explain how the source rectangle and the render coordinate system work together, then talk about the size and the constructor, furthermore show you how to use the viewport to create different layouts like a split-screen or a mini-map, as suggest in the description and at the end get a bit away from the direct manipulation of the sf::View and look at the convertCoords(…) function of a sf::RenderTarget.

At the bottom of the post you’ll find a ZIP file which holds a fully working example, demonstrating everything you’ll learn in this post.

The source rectangle

Since I don’t want to talk about the viewport yet but I’ll let it have its defaults value, which means that it will cover the whole window i.e. the whole scene will be rendered 1:1 onto the window.

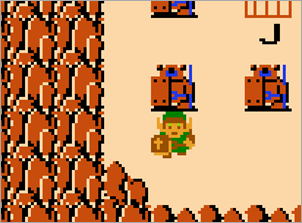

In the example above I’ve already moved the view to the point, where I’m rendering the separate sprite of Link. Link’s position in pixel is (1056, 640) but to get him centered, respectively the top left corner of him, I can’t just use what might seem intuitively:

view.setCenter(1056, 640);

(Of course you can set the view center to (0, 0) and then move to to (1056, 640) but we’re trying to understand what the center of the view is.)

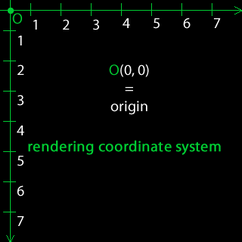

Since I’m assuming that you’ve already some knowledge with SFML, I’ll also assume that you know SFML is using a Cartesian coordinate system with a flipped Y axis. So the point (0, 0) can normally be found in the top left corner and then maximum x and y value can be found in the bottom right corner. If you’re working with images you’ll soon get comfortable with this system.

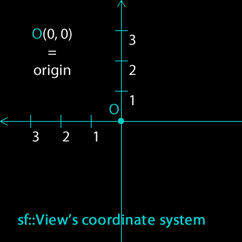

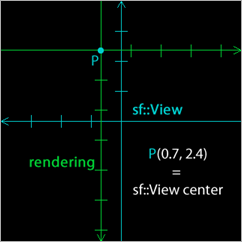

But now comes the center of view, which is in fact defined from the middle point of the display area. The view uses a Cartesian coordinate system too but this time the X axis gets flipped. In the end we have the point (0, 0) (also known as origin) in middle of the view, the maximum x and y values are in the top left corner and the minimal and negative x and y values are in the bottom right corner. What you’re now actually can set with setCenter is the where origin of the rendering coordinate system is put in the coordinate system of the view. I hope the following images will clarify the situation a bit.

The black square should represent the window and since we set the viewport to a fixed value the origin of the sf::View coordinate system will always be in the middle of the window. Here are the two separated coordinate systems:

If we combine them we get for example something like:

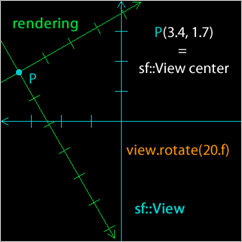

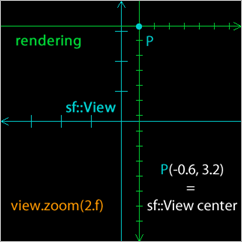

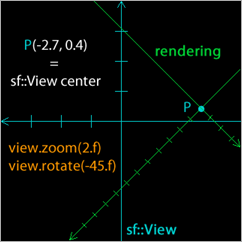

Then we have our two operations rotate() and zoom(). The last picture combines the two transformation:

I think it’s nearly impossible to explain this even better.

Note that in the images above, I’ve moved the rendering coordinate system around to get a few different variations. I guess most of the time it’s better to use the move() function since you won’t need to deal with where to place the origin point. On the other hand you really need to understand how sf::View works to use rotate() and zoom() because it’s not obvious that those transformation will happen around the sf::View origin i.e. the middle of the view.

You should keep in mind the introduced concept doesn’t just hold for a window it’ll work with any render target including sf::RenderTexture.

The size and the constructor

Before we take a closer look at the viewport we need to understand what the size of the view is and which parameters the constructor takes.

For now we’ve used the same size for the view as for the render target, this gives us a 1:1 projection. But what if we’d divide the size of both sides by two? From the observer perspective such a change would equal to using view.zoom(0.5f) but from the programmer perspective it’s something completely different. As we’ll learn in the next paragraph we can use the viewport to map the rendering stuff to a certain area on the window. Now if’ we’d apply the scene with the same size as before everything would get shrinked and eventually stretched if the ratio of the side isn’t the same anymore. This can create some wanted effects but mostly it would defeat the purpose. With setting a specific size, we’re telling the sf::View how big the view should get drawn while not making any visible transformations on the rendering part.

With that in mind it’s now easy to understand how to use the constructor.

sf::View view(origin.x, origin.y, size.width, size.height);

Where origin relates to a 2D vector of the origin in the rendering coordinate system and size relates to the sf::View size as discussed above.

The viewport rectangle

After we’ve seen most of the things sf::View can do, we want to generalize this even further. For now we’ve assumed we were using a window and rendered 1:1 onto it’s surface, but what if we wanted to display my stuff only on the lower right corner or use only the half left side? That’s where the viewport comes in.

The default values are sf::FloatRect(0, 0, 1, 1) which means the view covers 100% of the render target. So we got another rectangle which holds percentage values of the size of the render target. The first two values describe the position of the upper left corner and the last two values the lower right corner.

If you want to split the screen you’d need two different views for the left and the right side. Before you then draw to one side you’ll have to change the view on the render target first. To draw something to the other side, just set the second view and you’re good to go. This could look like this:

sf::View viewLeft(sf::FloatRect(0, 0, window.getSize().x/2, window.getSize().y));

viewLeft.setViewport(sf::FloatRect(0, 0, 0.5, 1));

sf::View viewRight(sf::FloatRect(0, 0, window.getSize().x/2, window.getSize().y));

viewRight.setViewport(sf::FloatRect(0.5, 0, 0.5, 1));

// ...

window.setView(viewLeft);

window.draw(leftSprite);

window.setView(viewRight);

window.draw(rightSprite);

With all the knowledge provided above you should now have a good understanding of why we divide the window width by two or why viewRight is defined with 0.5 as first argument.

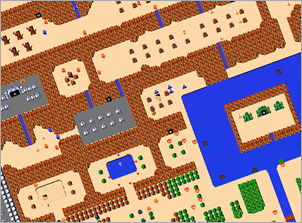

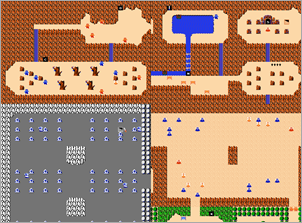

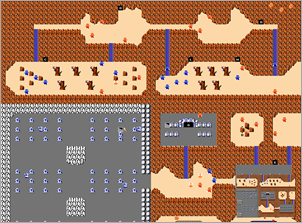

Another example I promised to show is how to create a mini-map i.e. a scaled down overview of the whole map. In practice it’s often better to construct it’s own mini-map rather than just scaling down the original one, since the quality can get fairly poor. But let us first test how it will really look like.

If you’re working with more dynamic data you’d probably need to render everything to a sf::RenderTexture and then extract the texture and render it twice. In this example we ignore those facts and just assume we’ve got a sprite with the Zelda map texture thus we can reduce the code to a few lines.

sf::View standard = window.getView();

unsigned int size = 100;

sf::View minimap(sf::FloatRect(standard.getCenter().x, standard.getCenter().y, size, window.getSize().y*size/window.getSize().x));

minimap.setViewport(sf::FloatRect(1.f-(1.f*minimap.getSize().x)/window.getSize().x-0.02f, 1.f-(1.f*minimap.getSize().y)/window.getSize().y-0.02f, (1.f*minimap.getSize().x)/window.getSize().x, (1.f*minimap.getSize().y)/window.getSize().y));

minimap.zoom(4.f);

// ...

window.setView(standard);

window.draw(map);

window.setView(minimap);

window.draw(map);

The mapPixel/CoordsToCoords/Pixel(…) function

As we’ve seen in the paragraph with the source rectangle it’s not very intuitive to work with those two coordinate system. It’s also pretty hard to determine by hand at which position for instance your mouse cursor is located relative to the view underneath. But why would you want to do this by hand, since SFML has already a build in function that will do the heavy lifting for you, namely mapPixelToCoords(…) and mapCoordsToPixel(…)?

There are two ways to use this function:

- Determine the relative position on the render target of the point P to the current view of the render target.

- Determine the relative position on the render target of the point P to a specified view.

This function can be very useful, e.g. you’ve moved around your view and now the user click on a point on the window. Just call mapPixelToCoords(…) and you’ll instantly know where on the moved view he clicked.

Complete demonstration

I’ve created a small application which packs up every introduced concept. The code isn’t the prettiest but contains a lot of more or less useful comments. I also provide a package that contains just the images presented in this blog post and since maybe some people want both, I’ve created one that contains everything.

- Code Package (392 KB)

- Image Package (801 KB)

- Full Package (1.16 MB)

If you have any questions/suggestions or found any mistakes/bugs/errors just let me know in the comment section!

Thanks a lot for your tuto eXpl0it3r

You’re very welcome! :)

Thank for this great explanation.

looks like converCoords() has been deprecated?

This, however, works for me (sfml 2.6.1) :

ss << "<" << pos.x << ", " << pos.y <\t<" << window.mapPixelToCoords(pos, standard).x << ", " << window.mapPixelToCoords(pos, standard).y <“;

You’re right! It didn’t make it into SFML 2 and I haven’t realized that I never updated it here. Thank you for pointing it out, will fix it ASAP! 🙂